Sunny Psychology

Trauma - Dissociation

Dissociation explained

The term ‘dissociation’ is used to describe many symptoms and they can be differently understood by different professions. In psychology we understand that dissociation is a symptom that comes as a result of having experienced severe trauma.

Simply put: dissociation means to dis-associate, disconnect or experience fragmentation and this disconnection sits on a continuum ranging from a random zoning out in traffic (mild symptoms, most people do this at times), to multiple personalities (severe symptoms).

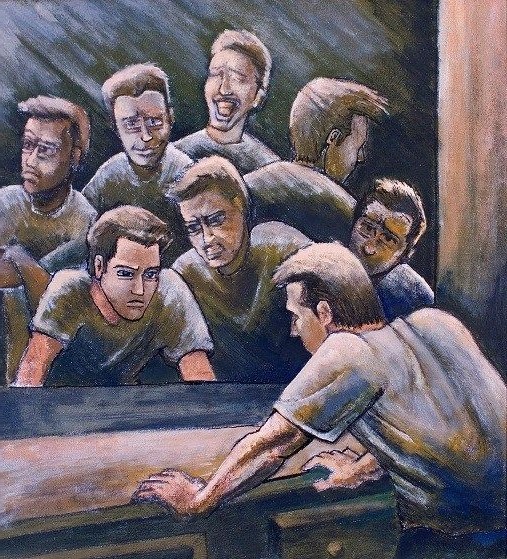

Please see the image below for a better understanding.

Sunny Psychology

Mild dissociation: temporarily going offline

Dissociation is the opposite of association, which means ‘bringing together’. When someone dis-associates, they separate things. In regards to mental health these ‘things’ are usually feelings, thoughts and memories.

For example, when someone sees a car accident, they may temporarily not be able to feel their body, because they ‘freeze’. They have disconnected from their body for a moment, because the body has gone into shock. It is like the Wi-Fi signal between the body and mind temporarily got disconnected and (part of) the body went offline. When their name is called or someone touches them, they are usually quickly able to come back to their body and eventually return to a physical state of balance. However, sometimes the ‘Wi-Fi-glitch’ gets stuck in the body and it may take longer to come back to that balance. This imbalance can last from minutes and hours to years and even decades.

Trauma

Moderate to severe dissociation: a result of trauma

The theory of ‘Structural Dissociation’ explains dissociation as a surviving mechanism to a manage a (range of) traumatic event(s). When someone experiences regular or even ongoing trauma, such as (sexual) abuse they may ‘go offline’ more often, sometimes to the point of splitting into multiple personalities to make it ‘easier’ to cope with the terrible events. (see the heading ‘Dissociative Identity Disorder’ below for more information) We call these personalities ‘parts’ or ‘selves’. The parts are a result of the brain’s amazing adaptive capacity to create ‘protectors’ that will help the person (usually a child) to cope with their harsh reality by keeping the memories separate from day-to-day functioning.

From a structural dissociation perspective, we all have parts, because we all have experienced trauma. Think about the time you started crying like a young child when your partner screamed at you, because it reminded you of your father yelling. Or the time you punched a wall and acted like an unreasonable 12-year old, because that is when you learned physical fights stopped your bullies.

A part is a fragment of ourselves that is stuck at a certain age, a bit like being stuck in time. This can lead to a range of dysfunctional behaviour(s). In session we often name the parts, such as ‘little self’, the ’17-year old self’ or the ‘scared self’.

“Survival mode is supposed to be a phase that helps save your life.

It is not meant to be how you live.”

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID): a fragmented self

Below is a list of more specific symptoms that suggests someone may be dissociative. Please note that all these symptoms by themselves can have multiple origins, such as substance abuse, brain injury and other neurological disorders. Just having such symptoms does not mean a person has a dissociative disorder. Additionally, this list is not exclusive.

Symptoms of dissociative identity include, but are not limited to:

- Time distortions (e.g. loss of time, time passing differently really fast or slow, no awareness of what day or year it is)

- Memory loss (e.g. no recollection of childhood memories, incl. important and happy events such as graduation)

- Hearing (childlike) voices

- Depersonalisation: alienation or estrangement from self and the body (e.g. feeling numb, foggy or blank, feeling not fully present, having memories but as if you watched the event instead of partook in in.

- Derealisation: estrangement from surroundings (e.g. people, place and things appear unfamiliar and even strange, the world can feel unreal).

Sunny Psychology

When to Assess for Dissociation?

Most mental health clinicians have received little or no training about dissociation and dissociative symptoms and questions about dissociative symptoms are absent from most standard clinical or psychological questionnaires and assessments. This causes many clinicians to fail to notice dissociative symptoms or to misclassify them in terms of a clinical diagnosis with which they are more familiar (e.g., depression, bipolar disorder, ADHD or psychosis), which can leave the matter untreated or mistreated for many years.

It is important to assess for signs of dissociation when a client reports or shows signs that are common in dissociative individuals, such as:

- Extensive trauma history

- Extensive treatment history

- Numerous prior diagnoses

- PTSD symptoms that haven’t changed despite treatment

- A prior diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder or Bipolar II

- Borderline Personality Disorder (either traits or prior diagnosis)

- Hearing voices

- Blank spells (signs of amnesia)

Assessment for dissociation is a standard part of the assessment of trauma treatment, such as EMDR Therapy. Validated questionnaires that specifically measure for dissociative features are the Trauma Symptom Inventory- Second Edition (TSI-2), the Dissociative Experience Scale- Second Edition (DES-II), the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ) and the Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation (MID).

“The single most important issue for traumatised people

is to find a sense of safety in their own bodies”

Treatment of Dissociative disorders

Treatment for dissociative disorders is focused on treating the root cause of the dissociation: trauma.

Treatment of any type of psychopathology can range from reducing symptoms to a manageable standard, to fully dissolving any symptoms. Treatment for dissociative disorders is focused on treating the root cause of the dissociation: trauma.

Effective treatment of complex trauma and dissociative disorders has three distinct, but interwoven phases:

- Establishing safety, stabilisation, and facilitating symptom reduction;

- Working through, and integrating traumatic memories; and,

- Integration and development of a healthy, flexible self

It can take months to years to work through phase 1, due to the lack of felt safety a client experiences as a result of their trauma. Successful achievement of the goals of Phase 1 is necessary for both clinician and client to be prepared to safely address trauma resolution in Phase 2 and develop a strong(er) sense of self in phase 3.

Dissociation

Treatment for mild to moderate dissociation

With mild to moderate dissociation treatment of the underlying trauma(s) can be highly effective and cease dissociative symptoms altogether. The main evidence based treatment for this is Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy. Other therapeutic modalities to reduce symptoms and build resources are Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), Neurofeedback, Yoga and other forms of somatic therapy and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Dissociation

Treatment for moderate to severe dissociation

At this stage (2022) there is no evidence based ‘cure’ for severe dissociation, including DID. This means that there is no known treatment that remedies symptoms altogether. There is no therapy or medication that will stop all the symptoms long-term. Some medication (e.g. like anti-anxiety medication) can reduce symptoms and bring temporary relief, but they don’t address and thus do not resolve the underlying cause of the problem. However, a lack of a cure is not a negative fact per se, because many clients do not want to lose their ‘parts/selves’ as they are part of who they are.

The focus of treatment of severe dissociation, including DID, is to significantly alleviate the symptoms of DID (e.g. flashbacks, mood swings, memory loss, impaired sleep) and develop a more integrated sense of self. Through awareness, resource building, processing memories and integration within the system severe symptoms can be reduced significantly. Living a functional and happy life with a dissociative disorder is certainly possible and thankfully many people have achieved this.